home

• Views: The Baur au Lac Magazine

• Yale Radio interview with Brainard Carey

• Joanne Mattera Art Blog: 60 Woman Artists over 60

• Joanne Mattera Art Blog: Art in the Time of Pandemic, Part 3

|

|

September 28, 2015Bookcovers

Water – 2 Degrees of Separation

Chester Township show

Chester Township’s Bascha Mon to show artwork

Posted: Friday, April 17, 2015 3:00 am

Bascha Mon

Chester Township artist Bascha Mon will show her works at the Port Washington (N.Y.) Library from May 2-31.

CHESTER TWP. – “WATER–2 Degrees of Separation” by township artist, Bascha Mon, will be on display from May 2-31 in the Main Gallery at the Port Washington Library, One Library Drive, Port Washington, N.Y.

Mon will attend a reception hosted by the Art Advisory Council in the Main Gallery from 2 to 4 p.m.,Sunday, May 3.

Mon has been creating and exhibiting art since 1971. She has had grants in painting, drawing and sculpture. She has received a grant from the New York Foundation for the Arts Relief Fund and was invited to a residency at the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild in Woodstock, N.Y., said a statement.

Mon studied at the Art Students League, the School of Visual Arts, Pratt and the China Institute and teaches privately and at the Hunterdon Art Museum in Clinton.

“My approach to art is both additive in process and intuitive in nature. My paintings, monotypes, sculptural installations evolve from the interaction of media and narrative,” she said. “I first visited the beautiful town of Port Washington to see the show of one of my private students, Tracey Luckner. I was delighted by the bodies of water passed en route. When this show was offered to me, I began to think how water had affected my life and my art and decided that could be the theme of this exhibition.”

Water Memories

Mon said that as a child, she spent summers at her grandparents’ farm adjacent to a lake and that later summers were spent on the Jersey shore.

“I learned to row and attended summer camp at lakes. The Caribbean and Cuba introduced me to new colors and beauty. Vacations in the Cape and Maine expanded my views of water and its capacity to reflect the light. The amazing changes associated with weather increased my respect for its potential to give pleasure and fear,” she said.

Mon said the 2004 Indonesian tsunami strongly informed her new work, leading to an extensive series: “TSUNAMI: LOSS.” Many works from the series are included in the latest show.

In 2011, the intensity of water had a personal effect when Mon’s studio was destroyed by Hurricane Irene.

“A new studio prompted me to change directions both in imagery and media. I switched from encaustic wax to oil paint. I allowed my early studies of Proust and Freud to influence a series of paintings both fanciful and experimental. I allowed my unconscious to guide my brush,” she said. “The combination of the highs and lows of the experiencing of water are explored in this exhibition.”

Contemplative pieces like “Adrift” combine with amusing works like “Beneath the Surface” with its lavender octopus.

“I hope that this wide-ranging group of works will appeal to a community itself so close to the water,” Mon said.

R&F Encaustic Paints

Q & A with Bascha Mon and Gallery Director Laura Moriarty

LM: What artists or movements have had the strongest impact on your work?

BM: Since I have been a working artist for over 40 years, many artists have become important to me. Long before I thought to study art, Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” and his “Cypress Tree” had a profound effect on me in terms of their color and texture and the compelling appearance that was based on reality, but seemed to be more related to a dream world. Before I started to study in NY at the Art Students League, my influences were limited to Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso, Monet, Bonnard and Cezanne. I was at that time not yet educated in modern art.

At school, I became aware of Egon Shiele who became my idol as a draughtsman and of Kandinsky, whose art and writings affected me profoundly. My drawing teacher, Marshall Glasier, was the first to involve me in the art of the Orient.

As I became more and more involved in experimenting with texture, Dubuffet was probably the artist who gave me permission to proceed. I was in love with the German Expressionists in school – Jawlensky and his brilliant colors; then Soutine and his swirling landscapes. After I left school, my first mature work to be exhibited in NY was compared in a review to Bonnard and Vuillard. I was duly complimented and recognized the influences.

LM: Did these influences change significantly at any point in time?

BM: The Indonesian Tsunami, with its monster waves and horrendous loss of life and livelihoods jolted me out of the personal and into the ‘other’. Until that point my art influences were mainly personal memories and my own life struggles. From that point to now, my art combines my personal passions with a new awareness and emphasis on world events.

Art for me is a confluence of received images such as the art of others, including films; and direct experience: friendship, home, children, travel, personal relationships and working in the studio, alone.

It is difficult to limit one’s influences only to visual artists.

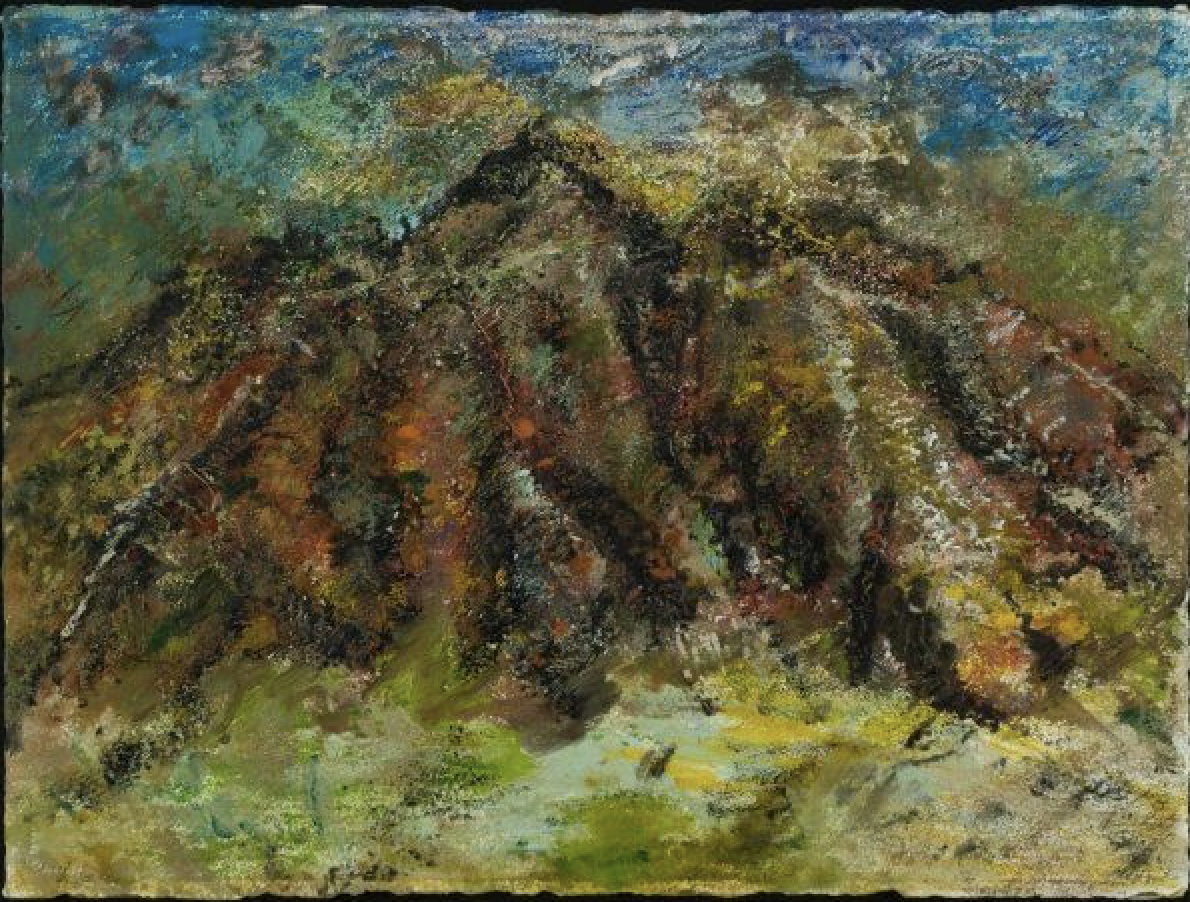

LM: What do mountains represent to you?

BM: Mountains entered my life psychologically and artistically as a child. A friend of my nanny, who was a painter, gave me a wooden box with oil paints; there were tiny tubes; tiny brushes; and a canvas board with a depiction of a mountain that I was to paint. Books and films centered on this theme combined threat and beauty: “Heidi”; Thomas Mann’s “Magic Mountain”; and Herzog’s “Fitzcarroldo” You should note here, that I had still never seen a mountain except in photos.

Thus mountains became a part of my fantasy life – both alluring and frightening. The concept of a mountain as a threat, a refuge, a barrier to be overcome represented certain aspects of my adult life. All of this is more psychological and literary than visual. I was not actually imagining myself in the mountains. However, after my parents died, I was able to take a 6 week trip to France, alone. This had been the dream of my life and it came true. I drove alone from Paris to the south of France. I crossed the’ massif centrale’ and was forced to drive up and then down the Gorge du Tarn. I do not know when I have ever been so frightened (except on a roller coaster). The road had no room for a car that might come from the other direction and no safety rail. I was incapable of looking at the view. When I reached the bottom, my knees were trembling so that I couldn’t get out of the car. BUT, I had done it. I had crossed a mountain physically and felt a surge of renewal and strength. This accomplishment began to affect my art. I was not painting mountains then, but the joie de vivre of at last being in France and visiting the homes and studios of artists whom I loved. I had been to Mont St. Victoire and to Cezanne’s studio. I brought back with me a small stone taken from the base of that mountain which he had painted so many times.

In 1991, a purchase prize in the Osaka Triennale took me to Japan. I went first to Tokyo. In the bullet train to Osaka, I longed for a view of the sacred Mt. Fuji. The business man in the adjacent seat told me,” it is very unlikely, since Mt. Fuji’s tip is always shrouded in mist.” However he told me when to look – et voila- the majestic mountain appeared. Its beauty had been praised in poems and paintings for generations. My seat-mate told me that such an unlikely sight presaged good fortune in my life. Certainly the trip to Japan proved that fact. The gardens of Kyoto affected me profoundly and on my return, I became a sculptor. I planned and executed a complete Japanese garden, the rocks, bridge, stepping stones, etc. carved from Styrofoam and painted with acrylics.

My research uncovered the famous “Fujito Stone”. The story entranced me and I carved a facsimile of that group – my large mountain rock and then a smaller mountain rock grouping. This period of my artistic life was meditative and spiritual. I do not think that the current, more political work could have had the necessary passion without the earlier Japanese influence. Although it was not in my consciousness at the time, I think that the painting titled “White Mountain” comes closest to my feelings of the imperious and beautiful Mt. Fuji. In my series, this is the mountain under attack. It was shown as an installation, with “Battlefield” on a platform beneath it.

Once I had decided that the imposing mountain of South Waziristan was impossible for me to ignore, all of the above influences became essential to approaching my new subject. I think that without all that came before, I might never have embarked on the series of mountain paintings that are part of this interview. The solo exhibit of “Mountains, Barriers and Poppy Fields” began not with my profound antiwar attitude, but my own psychological disposition in the face of obstacles. For me to become an artist, was at first an insurmountable mountain to be conquered.

LM: Do you find painting a satisfying medium through which to express political concerns?

BM: This is a particularly difficult question, as I do not create paintings expressly to portray my political concerns. Ideas are elicited through images and articles seen in the daily newspapers and then filtered through my artistic imagination. I do not start with a political premise and then decide to “illustrate” it. It might be helpful here to quote from a prominent artist and writer who supplied the essay for my catalog of “Mountains, Barriers and Poppy Fields”, Carl Hazlewood.

He has known my work for over 30 years and is able to elucidate more poetically than I, the varied components of my work.

“Far away from the actual theatre of the Afghan war, in her quiet corner of New Jersey, Bascha Mon has turned landscape tradition, informed by the lessons of modernity, into an effective medium of protest. As Sharon Memis, the Director of the British Council in the United States argued recently, “The arts can play a pivotal role during war or conflict because they encourage understanding between different cultures, helping foster trust, prosperity and stability.” “So, amidst the terror and absurdities, lay the absolute beauty that makes us human. Bascha Mon’s art, luxuriously textured in form and concept, is proof, if such is needed, that contemporary painting, conflicted though it may be, retains the ability to engage our senses, our emotions and intellect as not many other forms of creative endeavor could.” Copyright Carl E. Hazlewood – 2011.

Carl has expressed my views far better and more fluently than I. It is important to me that my works be considered first as art and lastly as a political statement.

LM: Is the response that you get about your work from the art world different from the response you get from the general public?

BM: Critics, Museums, Galleries, etc. can make your work more valuable to collectors. Positive reviews and shows may lead to more exposure. Peer response may be constructive and informed. On the other hand — is the public all that different?

Anyone who takes the time to respond to my work, whether in an email, a phone call, or simply by chatting with me at an opening is making me very happy. I want my art to communicate – if there is a response then it has a profound effect on me –this is very satisfying.

My students — are they the art world or the public or both at the same time? They are of great importance to me. They are the most supportive followers of my work and frequently the ones who purchase my art. Reviews are great, but they are most often only read by other artists. There is seldom any direct feedback. Yes, one wants the attention and the affirmation of the “knowledgeable” art critic. But how often have we, as artists, read reviews of art that we have seen and completely disagreed with the critic’s comments.

Now, let us consider the effect of the Internet. Here one may be exposed to the art world and the general public simultaneously. Facebook actually is a wonderful way to receive feedback from the art world as well as the general public. I have personally benefited from responses from artists all over the world who would not have had any other way to see my art. Websites offer another avenue for people either in the art world or the general public to see my work.

Art is subjective and I think that ANY response is important.

Whether it is critical response or private is not the issue (except when it comes to a dollar valuation created by an auction house). What really matters is that as many people as possible see the work. A bad review is perhaps better than being ignored. We artists are sensitive creatures and being ignored is the hardest part. When our work is on exhibit and people stop and study it and stand and look for a long time, why should it matter if they belong to the art world or the general public? They are looking and maybe caring. We have an audience. Our art is not living alone in our studio. And, even if that is where it stays, we will still continue to make art. Art is our way of life. Art speaks to us. If it can speak to others as well, that is a plus. But, their actions or decisions will not cause us to cease creating.

Here I would like to quote from three important contemporary artists’ interviews:

*William Kentridge “……..make the people who already love what you do your primary audience……”

*Tony Ourlser “…..you have to validate yourself from the inside…..”

*Victoria Vesna “…..The trick is to create art works that actively stand up in an art environment with all the value systems that apply there and still speak to a larger audience.”

So, in conclusion, my feeling is that one must make art of the highest possible quality and not be concerned about the vagaries of the market place or the art world. In the long run, we make art because we must.

ARTIST STATEMENT

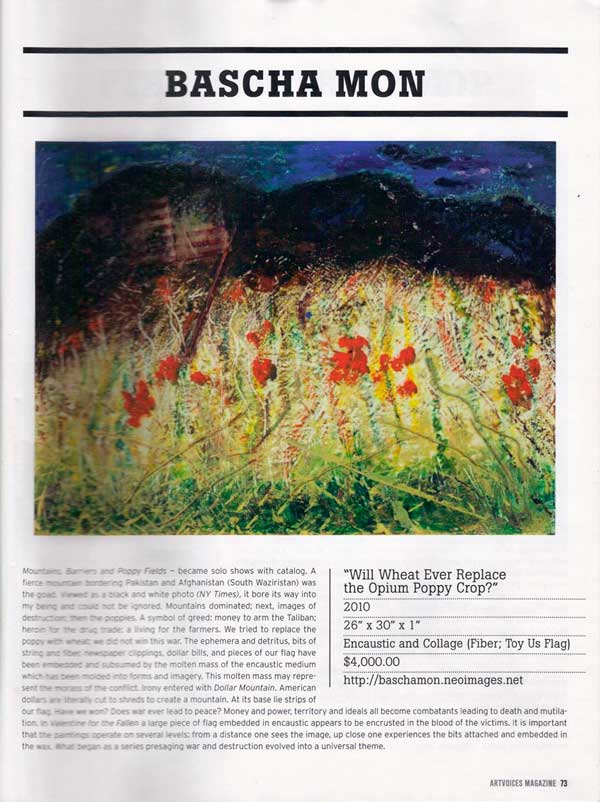

An ominous mountain looms between Pakistan and Afghanistan in South Waziristan. Its black and white photo (clipped from the NY Times) hung in my studio for months. It tantalized and provoked me, but could not be ignored. Such direct representation and symbolism had not previously been present in my work. Could I correlate my love of color, texture, light and form with an anti-war attitude using this mountain as a fulcrum?

How freely could I change the original form and color to create a series that might seduce with its beauty and still convey the deplorable meaning – the barrier, both physical and psychological presented by this mountain?

Encaustic paint has been my medium since the workshop taken with Laura Moriarty about 10 years ago. Through this choice, I accepted the challenge to create highly textured work that could have been more easily executed in oil. Challenge beckons to me. I have never physically climbed a mountain– I have a phobia about heights. But, in my art, all dares are possible. In painting or sculpture I may visit places not available to my everyday world. This war, the deaths and maiming of multitudes, brought the same passions to my work as those imparted by the Indonesian Tsunami (and that engendered Tsunami: Loss.) The series evolved leading through the mountains to paintings of conflagration. Next, I broached the dichotomy of beauty in poppies. They lead to further annihilation both by the opium/heroin produced and its byproduct- money. Money tinges all aspects of war. Thus dollar bills entered my work. When collage can add a more tangible and/or provocative aspect, I use it. There are no absolutes or rules to my working life as an artist.. Any medium: painting, sculpture, digital prints, drawings, installations. I will employ them all at one time or another. Just as that majestic and frightening mountain lured me into this series, I remain open to all stimuli that will express my fears and my desires.

Will war ever lead to lasting peace? This unanswered question may continue to influence my art through as yet unimagined and seemingly unrelated forms.

My art cannot change the course of nature or war, but I will persist in a belief in the future. The ambiguity of life extends to the possibilities of art.

ArtVoices Magazine

December 15, 2014Uncategorized

Gallery takes viewers on excursion to the abstract

, By EILEEN WATKINS

If you like your art truly abstract, you should love the latest three-person show at the Visitor Center of Thompson Park in Lincroft.

Few of the works ever come close to images of reality, the nearest being when the paintings by Bascha Mon suggest interiors. The average viewer might argue that, for such a large exhibit, this borders on too much abstraction, with nothing to balance the effect.

The media and styles do vary, however, and pleasantly.

Gloria Cernosia du Bouchet of East Brunswick works with collographs. Subterranean images are(

laged,” using a prominent strip of gauze to create a sweeping movement.

“Hearts and Flowers” provides the symbolic reference points of a row of yellow hearts, an abstract garden and the faint outline of an iron gate; “Home at Last” suggests the frames of doors or windows. But in general the viewer will be content to absorb the sunny, upbeat feeling the works create without making literal translations.

Most of the mixed-media pieces by Natalie Craig of Long Branch are included in her “One to One: A Suite of Formalities.” Using pastel, pencil, thread and vellum, she takes advantage of the natural irregularities of the materials and their interaction.

Craig colors the background material, sometimes a sheet of newspaper, with pastel of charcoal, then places vellum over it for a distant, blurred effect. Sometimes the vellum is attached with glue, at other times it is sewn on.

A “foreground” is created when the artist draws or paints sharper and more brightly colored lines on top of the vellum. Sometimes these lines are short and straight and can scarcely be distinguished from the stitching.

When you are in the mood for a total excursion into abstract, drop down to Thompson Park, on Newman Springs Road in Lincroft. The three-artist show remains on view through May 28.

A/it Opening

evoked by her groupings of hard-edged bands that contain dense black-and-white or brown-and-white textury patterns.

“Eight on the Richter Scale” involves seven of these bands, or narrow rectangles, standing vertically, while a red line runs down and through them like a rupture. Several works in a series called “Temporal Steps” portray either vertical or horizontal groupings of these forms with one band slightly out of kilter, and contrasting in color, either solid black or patterned brown.

* * *

A few of the prints use more solid areas of black and white, with hard lines only at the outer edges. They contain churning patterns and have titles such as “Maelstrom” and “Norfolk Landscape”; one divided by a continuous white “tunnel” is called “Kinks, Curls and Convolutions.”

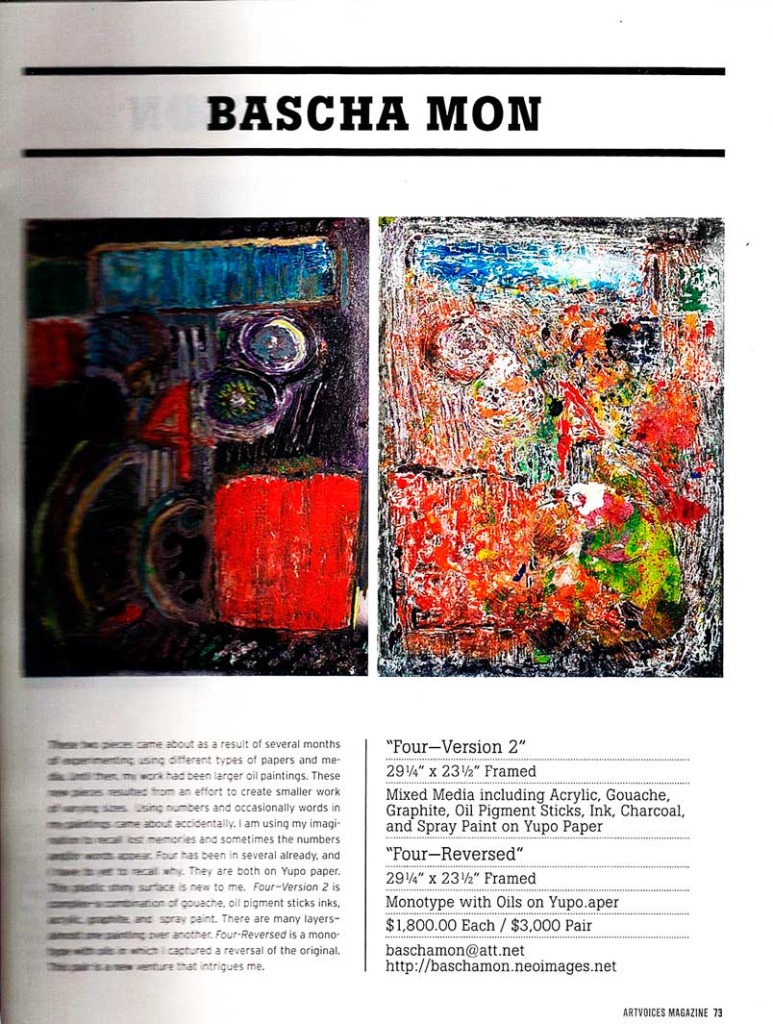

As a change from this crisp technique, painter Bascha Mon of Long Valley uses soft tones and misty outlines. Her canvases and mixed-media works have a general resemblance to rooms and occasionally exteriors of buildings, distorted as in a memory.

* * *

Her large oils such as “Sissy, Cabbages and Friendship,” “Cross-References” and “Ritual” use loosely geometric areas, chiefly quadrangles with slanting vertical borders. The colors are all soft and similar in value; various depths and textures are indicated by stripes, curlicues and speckles, as well as by painting one tone over another.

Mon adds bits of canvas and paper to her larger works only with restraint. “Flight” is the most “col-

A Group Art Show

Tomasulo Gallery

December 13, 2014Uncategorized

Review by Carol Rosen

As an artist, Bascha Mon ‘s approach to her work is both additive in process and intuitive in nature. Paintings, monotypes and sculptural installations evolve from the interaction of media and narrative, sometimes subtly, sometimes explicitly. Recent works in encaustic relate both to the layering of brush strokes of color in her early paintings as well as to the use of robust colors which developed in the later series of plaster heads. While one series of installations reflects a trip to Japan and the impact of its visual traditions upon her, another combines sculptural heads with a collection of small painted chairs, tapping into our experiences of the world as children. As her work continues to evolve, it references both painterly and sculptural concerns and, as always, the world which she inhabits.

Having come to teaching later in life, Bascha Mon has brought a wealth of information to her students along with a love of all things visual, so evident in her own work. Her receptivity to other cultures, the performing arts, and nature, along with her own personal background, have been combined with the need to creatively express these experiences .Most significantly, she has been able to pass this enthusiasm along to her students, often using experimental approaches to develop their innate talent and to stimulate their own explorations. By presenting the unexpected, the ordinary is re-evaluated and becomes something other than what it was.This can take the form of using touch, smell, sound and taste to stimulate creativity, or collaborative efforts which enable students to interact and enlarge their individual experiences in the creation of a new image. Students are also constantly exposed to other artists whose works seem pertinent to their own explorations of form, color or ways of looking at the world. Bascha Mon has encouraged her students, not only to look and see, but to develop and accept their own creative voices.

NY Times: Objects, Found and Made, Add Up to Sculpture

THE NEW YORK TIMES, SUNDAY, JUNE 7, 1998

ON T H E T O W N S

ART REVIEW

Objects, Found and Made, Add Up to Sculpture

Several plaster heads, many with antennae and painted with metallic pigments. They result from Ms. Mon’s recent foray into making more conventional sculpture. They have a goofy presence, like space aliens, and certainly jar the contemplative aspect of the rest of the piece.

This garden was to be used last year as the set for a performance piece at Aljira: A Center for Contemporary Art in Newark. The performance never took place, but an antique Japanese umbrella that would have been part of it turns up in “A Collagist’s Diary: Wandering and Wondering,” an amalgam of objects compactly arranged to resemble a large painting. Indeed, it recalls the work of the 19th-century American painters William Har-nett and John Peto, who made con-

By WILLIAM ZIMMER

THE sculptures of Bascha Mon are energized by opposition. Ms. Mon puts disparate objects together in ways that are at once audacious and subtle, sophisticated and ingenuous, compulsive and calculated. Made of both found and created objects, they are repositories of memories: Ms. Mon’s personal fixed memories, often potently intersecting with the collective memory.

Eleven of her sculptures are currently at Tomasulo Gallery at Union County College here, where they ramble over a gray carpet, lean against the wall or just perch on pedestals. Each work is a fresh challenge, but viewers are also reassured by the presence of several constants. Chief among, them are rocks, which have weight and solidity, and mirrors, which convey ephemerality and illusion, and the artist uses this contrast to perpetuate illusion. In the exhibition, real rocks are mixed in with artificial ones, while mirrors are employed to extend a work, make it seem larger than it is or reveal another side of a component part.

Ms. Mon was born and reared in Newark, where her parents ran a store that sold notions, lace and other decorative trimmings, which may play a part in her readiness to embellish everyday objects. The first work a viewer might encounter, and an especially inviting one, is “Cow Redux,” a stacking of objects culminating in a charcoal drawing of a cow’s head that Ms. Mon made 27 years ago. (Ms. Mon has been a painter most of her career, and recycled two-dimensional work frequently appears in the exhibition.) The drawing is accompanied by a watering can that was her father’s, a manure spreader, a scrap of burlap she found near a cemetery, a metal box in which milk bottles were kept, and a wooden crate holding a shard of red glass from a taillight, a souvenir of a car accident, along with a small smooth wooden dowel that is there ‘just for esthetic reasons, to balance the broken glass,” Ms. Mon remarked in a conversation at the gallery.

The transforming event of her life and career, she says, was three weeks spent in Osaka, Japan, in 1991, a result of winning a prize in the Osaka Triennial. She seems to have quickly soaked up Japanese culture and esthetics, an orientation that, she says, is responsible for the contemplative nature of much of her work. The’two most extensive works in the show have strong Japanese motifs.

“Visitors to the Illusory Garden” mimics a rock garden, but the tall, craggy forms and the smooth slabs evoking steppingstones are painted plastic foam. On the slabs are fixed amazingly sharp pictures of manhole covers, the design of which is evidently a high art in Japan Ms. Mon savors the coexistence of a garden and a sewer, and to complicate the mix further there are several convincing trompe 1’oeil arrangements of commonplace but often unrelated objects. The nearly closed umbrella is posed against a roof taken from a Japanese doll house. These, along with a sheaf of bamboo, a bamboo stool hung upside down from a rope, and the 1950’s-style shade from a floor lamp that Ms. Mon had in college, turned upside down to become a bowl, are other things to ponder in the crowded work. A picture frame holds a Japanese newspaper, along with recycled drawings, and a clear plastic bag of dead leaves hangs from the frame. One rather grubby plaster head is on the scene as an observer.

(ANOTHER entry from “A Collagist’s Diary” is an open suitcase, also an artifact from Ms. Mon’s college days, with a round mirror inside the lid. It is filled with a nest of brightly, even garishly colored neckties, along with the tattered remnant of an American flag found near a cemetery. The coiled neckwear is weighed down by a real rock, seemingly to prevent it from slithering away. Ms. Mon uses such an arrangement of ties as a still-life subject in painting classes she teaches at the Hunterdon Museum of Art in Clinton and the New Jersey Center for Visual Arts in Summit.

The smaller works, too, reflect the events, large and small, of Ms. Mon’s life. A viewer senses that Ms. Mon has embarked on a continuing project that can never end. Nor can it be neatened up and fitted into a tight category of art. Many artists enshrine objects from their past, but Bascha Mon’s knack for poetry, and her sense of abandon, set her apart.

BASCHAMON

Tomasulo Art Gallery Mackay Library, 1033 Springfield Avenue, Cranford

Through June 18. Hours: Mondays and Saturdays, 1 to4 P.M.; Tuesdays through Thursdays, 1 to 4 P.M. and 6 to 9P.M.

(908) 709-7155

Family Portraits

Bascha Mon

FAMILY PORTRAITS

For quite some time critics said that nothing “new” could be created in the world of art. All the isms had been done – we were left to repeat the past in the age of pluralism. It is now clear, however, that important artists always have something new to contribute. Like a fingerprint we all have something no one else has. Bascha Mon has achieved this singularity in her work and she has inspired it in her students.

The human head is a subject that goes back to the very beginnings of what we know about our visual history. Humans have portrayed the head in an endless variety of ways. Today, technology being what it is, we can draw from almost every culture and time period ranging from prehistoric cave paintings, the ancient Greeks, Romans, Egyptians and Asians to the tribal arts of the Americas, Africa and Oceania. Nearly all these sources seem combined, recombined, reduced and worked into a pure essence of the human head in Bascha Mon’s sculpture and paintings. With pigments that seem drawn from the earth and rough-hewn surfaces that feel worn to a shadow of a former complexity, Mon’s heads look as if they have been dug up from an ancient past. The simple geometry of prehistoric Cycladic heads are buried in her surfaces as are the classical Greek busts, Asian warriors, the heavily worked, elongated heads of Giacometti, the dark and rueful heads of Roualt, and the simple planes of Modigliani’s women. This syntheses makes the viewer linger over a sense of recollection that is both subconscious and deeply personal.

Ms. Mon’s examination of the human head is deeply compelling for the same reasons she is a successful teacher. She is able to guide her students away from preconceived notions about art into a willingness to tap into and trust their less conscious and unique gifts.

Kristen Accola 2003 Exhibitions Curator – Hunterdon Museum of Art

N.Y. / REGION | ART REVIEW

ART REVIEW; Objects, Found and Made, Add Up to Sculpture

By WILLIAM ZIMMERJUNE 7, 1998

Continue reading the main storyShare This Page

Share

Tweet

Email

More

Save

THE sculptures of Bascha Mon are energized by opposition. Ms. Mon puts disparate objects together in ways that are at once audacious and subtle, sophisticated and ingenuous, compulsive and calculated. Made of both found and created objects, they are repositories of memories: Ms. Mon’s personal fixed memories, often potently intersecting with the collective memory.

Eleven of her sculptures are currently at Tomasulo Gallery at Union County College here, where they ramble over a gray carpet, lean against the wall or just perch on pedestals. Each work is a fresh challenge, but viewers are also reassured by the presence of several constants. Chief among them are rocks, which have weight and solidity, and mirrors, which convey ephemerality and illusion, and the artist uses this contrast to perpetuate illusion. In the exhibition, real rocks are mixed in with artificial ones, while mirrors are employed to extend a work, make it seem larger than it is or reveal another side of a component part.

Ms. Mon was born and reared in Newark, where her parents ran a store that sold notions, lace and other decorative trimmings, which may play a part in her readiness to embellish everyday objects. The first work a viewer might encounter, and an especially inviting one, is ”Cow Redux,” a stacking of objects culminating in a charcoal drawing of a cow’s head that Ms. Mon made 27 years ago. (Ms. Mon has been a painter most of her career, and recycled two-dimensional work frequently appears in the exhibition.) The drawing is accompanied by a watering can that was her father’s, a manure spreader, a scrap of burlap she found near a cemetery, a metal box in which milk bottles were kept, and a wooden crate holding a shard of red glass from a taillight, a souvenir of a car accident, along with a small smooth wooden dowel that is there ”just for esthetic reasons, to balance the broken glass,” Ms. Mon remarked in a conversation at the gallery.

The transforming event of her life and career, she says, was three weeks spent in Osaka, Japan, in 1991, a result of winning a prize in the Osaka Triennial. She seems to have quickly soaked up Japanese culture and esthetics, an orientation that, she says, is responsible for the contemplative nature of much of her work. The two most extensive works in the show have strong Japanese motifs.

Continue reading the main story

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

”Visitors to the Illusory Garden” mimics a rock garden, but the tall, craggy forms and the smooth slabs evoking steppingstones are painted plastic foam. On the slabs are fixed amazingly sharp pictures of manhole covers, the design of which is evidently a high art in Japan. Ms. Mon savors the coexistence of a garden and a sewer, and to complicate the mix further there are several plaster heads, many with antennae and painted with metallic pigments. They result from Ms. Mon’s recent foray into making more conventional sculpture. They have a goofy presence, like space aliens, and certainly jar the contemplative aspect of the rest of the piece.

This garden was to be used last year as the set for a performance piece at Aljira: A Center for Contemporary Art in Newark. The performance never took place, but an antique Japanese umbrella that would have been part of it turns up in ”A Collagist’s Diary: Wandering and Wondering,” an amalgam of objects compactly arranged to resemble a large painting. Indeed, it recalls the work of the 19th-century American painters William Harnett and John Peto, who made convincing trompe l’oeil arrangements of commonplace but often unrelated objects. The nearly closed umbrella is posed against a roof taken from a Japanese doll house. These, along with a sheaf of bamboo, a bamboo stool hung upside down from a rope, and the 1950’s-style shade from a floor lamp that Ms. Mon had in college, turned upside down to become a bowl, are other things to ponder in the crowded work. A picture frame holds a Japanese newspaper, along with recycled drawings, and a clear plastic bag of dead leaves hangs from the frame. One rather grubby plaster head is on the scene as an observer.

New York Today

Each morning, get the latest on New York businesses, arts, sports, dining, style and more.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Receive occasional updates and special offers for The New York Times’s products and services.

SEE SAMPLE MANAGE EMAIL PREFERENCES PRIVACY POLICY

A NOTHER entry from ”A Collagist’s Diary” is an open suitcase, also an artifact from Ms. Mon’s college days, with a round mirror inside the lid. It is filled with a nest of brightly, even garishly colored neckties, along with the tattered remnant of an American flag found near a cemetery. The coiled neckwear is weighed down by a real rock, seemingly to prevent it from slithering away. Ms. Mon uses such an arrangement of ties as a still-life subject in painting classes she teaches at the Hunterdon Museum of Art in Clinton and the New Jersey Center for Visual Arts in Summit.

The smaller works, too, reflect the events, large and small, of Ms. Mon’s life. A viewer senses that Ms. Mon has embarked on a continuing project that can never end. Nor can it be neatened up and fitted into a tight category of art. Many artists enshrine objects from their past, but Bascha Mon’s knack for poetry, and her sense of abandon, set her apart.

BASCHA MON

Tomasulo Art Gallery

Mackay Library, 1033 Springfield Avenue, Cranford

Through June 18. Hours: Mondays and Saturdays, 1 to 4 P.M.; Tuesdays through Thursdays, 1 to 4 P.M. and 6 to 9 P.M.

(908) 709-7155

"MOUNTAINS, BARRIERS AND POPPY FIELDS"

"MOUNTAINS, BARRIERS AND POPPY FIELDS"

© Carl E. Hazlewood – 2011

What is beauty? If it can be found in the truth of one person’s articulate feelings about continuing tragedy, then here it is on view for all to see in ‘Mountains, Barriers and Poppy Fields.’ This exhibition by Bascha Mon, contains personal truth embedded in a landscape of grandeur and despair. It all began with the event of 9/11, on a morning of absolute clarity. That elemental perfection underscored a drastic failure of human potential. The faultless blue skies became smeared with ashes of ambition, anger, and fanatic self-righteousness. Thus the suffering continues today.

Bascha Mon is an accomplished artist who has been at work for over forty years. Her recent practice has been dedicated to a quietly resonant vein of painting. These works, rich in texture and color, employ an innovative approach to applying the ancient medium of encaustic. Using sheets of heavy archival paper as ground, her paintings often incorporate a variety of material that invests each piece with emotional, cultural, or political meaning. The form is ordered, not by current artistic fashion, but by the artist's personal values and spiritual need—spiritual in the sense that her oeuvre is driven by something beyond material values or specifically art world issues and tendencies. Ms. Mon has chosen to live in a bucolic area of New Jersey. From her studio she looks out onto calm fields replete with evidence of flora and fauna alive and thriving. However, in her current art, nature has become suspect, an ambivalent beauty, and a recalcitrant symbol of our moral and physical frailty.

“During times of war, artists help us remember this: if we knew each other more, we might damage each other less. Across distances when we often perceive each other askance, at angles slant and sharp, we can forget what we instinctively know - that seeing another as an 'other,' separate and quite apart, can lead to our collective end…” - Sarah Lewis

While Bascha Mon's current project, ‘Mountains, Barriers and Poppy Fields.’ has been instigated as a response to a specific ongoing conflict in a particular part of the world, the artist's past work has often been driven by a humanistic sensitivity along with her need to understand and bridge cultural barriers. Mon visited Osaka, Japan, in 1991, after winning a prize at the Osaka Triennial. The contemplative installations she made upon her return to the US became subtle meditations on the poetry of Japanese environmental aesthetics. And in a way, Ms. Mon's images have always been more about poetics than reportage, whether responding to the nuances of Japanese culture, or to a tragedy such as the tsunami of a few years ago—a natural event that shocked the world with its immense devastation. In either case, her images function via the engine of passion. And it is not particularly about romanticizing the far away Afghan war; 'Mountains, Barriers, and Poppy Fields' have become an elegy to one person's feelings via the weight and measure of vision combined with lucid form. Goya's, 'The Disasters of War' went to a dark and terrible place to show directly the horrors of war. Bascha Mon has chosen to underline the evident darkness by 'speaking' to the beauty of light and color. Again, It is somewhat of a metaphysical journey, if by that we mean the inchoate striving of human beings to transcend death despite our constant tilting toward the darker corners of the heart.

“But death cannot conquer a man who has shaken off his dust; it is powerless against eternity. The wind, life, flow from the infinite, the moon drinks the breath of life, the sun drinks the moon, and the infinite drinks the sun.” - From The Mahabharata.

The mountain that is the major subject of many of these works is a physical place. It is also a metaphor for those obstructions, which separate people; it's the shadow of death. It is implacable in its stolid presence. Bascha Mon came upon the image of this threatening prominence as a black and white photograph in the New York Times, and kept it tacked to her studio wall for a long time. The mountain stands between Pakistan and Afghanistan in South Waziristan. She notes, “At first, I couldn't imagine being that realistic, but then I thought about Cézanne and how he painted so many versions of Mont Sainte Victoire (...) but the idea was planted that there could be variations on the mountain.”

In his series featuring Mont Sainte Victoire, Cézanne pursued ways to assert an absolute equivalency of dynamic structure using paint on canvas. But Ms. Mon is less interested in the formal aspects of constructing a painting than in building up its symbolic configuration. Not that she is unconcerned with how a picture is made. She has already considered and mastered the plastic and formal means required to present her pictures as effective and satisfying aesthetic objects. The encaustic medium she prefers for this series has an assertive yet malleable character. Centuries older than the invention of oil paint on canvas, the most memorable use of the encaustic medium was the vivid Fayum memorial portraits of the dead found in Egyptian tombs dating from about the 1st to 3rd century in Hellenistic Egypt. While those portraits have found a way to ensure the human desire to live forever, at least in memory, Mon’s contemporary images, also concerned with death, and just as vivid, are memorial pictures of a sort. They have become cultural mementos that implicate us as thinking people and as responsible Americans. In this way they signal endings, beginnings... and possibilities for change. Technically, Bascha Mon eschews the jewel-like translucent quality of the medium for dynamic encrustations worked into a range of pictorial effects. Fluid when heated, the pigmented wax quickly hardens, incorporating a magnetic accretion of ‘significant’ material that can suggest the equivocal and poignant aspects of human greed and desire. Coupled with the titles, as specific or metaphoric language, they indicate what we know or think we know about the area geo-politically and in human terms.

Paintings such as, ‘Conflagration’ and ‘Exploding Building,’ depict flames and burning buildings inspired by news photographs from the conflict. These are considered the ‘Barriers’ of the exhibition’s title, since, as the artist said, ‘through destruction we have not eased the burden of war but caused more devastation and death.’ For Bascha Mon, Poppies have become symbols for ‘the greed and anguish of war...’ because money from the cultivation of the poppy fields enriches individuals involved in the heroin trade, and funds the ongoing war.

The most political aspect of the works on view is their titles, which tend to implicate us, as much as they suggest sorrow and concern regarding the situation for those who have to exist in that beautiful, distant, and desolate place of our imaginations. The specific titles of her pictures reflect our individual confusion and American complicity in this relentless conflict.

There are actual red paper poppies embedded in 'The American Legion Veterans' Poppy Field #4.' Part of a United States flag shows in the sky. ‘Will Wheat Ever Replace the Opium Poppy Crop?’ is the rather plainspoken title of an encaustic with found toy, US flag, and bits of fiber and straw on paper. Torn and cut up dollar bills with more fragments of American flag comprise 'Dollar Mountain.' ‘Battlefield’ lies flat beneath the exquisitely painted, ‘White Mountain' — an intriguing compound installation.

Far away from the actual theatre of the Afghan war, in her quiet corner of New Jersey, Bascha Mon has turned landscape tradition, informed by the lessons of modernity, into an effective medium of protest. It is, to be sure, nothing so simple as a political protest. As Sharon Memis, the Director of the British Council in the United States argued recently, ‘The arts can play a pivotal role during war or conflict because they encourage understanding between different cultures, helping foster trust, prosperity and stability.’ So, amidst the terror and absurdities, lay the absolute beauty that makes us human. Bascha Mon’s art, luxuriously textured in form and concept, is proof, if such is needed, that contemporary painting, conflicted though it may be, retains the ability to engage our senses, our emotions and intellect as not many other forms of creative endeavor could.

_________________________

NOTES AND REFERENCES Bascha Mon is quoted in each case from letters to the author, January 2010. Sarah Lewis discusses war in a Facebook update, November 30, 2010; her play is part of ‘The Great Game,’ a series of 12 contemporary British and American plays tracing 150 years of foreign engagement in Afghanistan. Sharon Memis’ quote is taken from her article, ‘War, culture, and ‘the great game,” in Foreign Policy magazine, online, September 14, 2010. The Mahabharata,’ is a major Sanskrit epic poem of ancient India.

Mountains and Barriers #1 2010 - encaustic on paper

|

|